The world's weirdest border?

jotily/Getty Images

jotily/Getty ImagesPerhaps the world's most complicated boundary, a narrow bike trail offers a window into a region that has been the battleground of Europe and is where culture and geography intersect.

Nicolai Meyer stepped away from his restaurant's deep fryer to offer a quick lesson in geography.

"We're in Belgium," he explained, then pointed through the window. "The road is Germany. Then it's Belgium. Then Germany." The entire area he described spanned perhaps 50m.

I picked up one of his chips, which he assured me was a true Belgium frite, dipped it in mayonnaise and took a bite as I tried to make sense of this patchwork quilt borderland.

What may be the world's most complicated boundary centres on a narrow ribbon of bike trail. Its history offers a window into a region that at times has been the battleground of Europe and an area where culture and geography intersect.

The cycling route follows an 1899 railroad called the Vennbahn, or Fens Railway, which connects the city of Aachen, Germany, with Luxembourg. Built by Germany's Prussian State Railway to haul coal, iron and steel, the railway fuelled industrial growth and prospered through World War One, when it was used to carry military supplies.

When hostilities ended, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles awarded Belgium contested German land, along with the railroad and its tracks that connected it. That included a 28km corridor that left several pockets of German land completely cut off from the rest of the country. One section was annexed by Belgium and later returned to Germany in 1958, but five others remain as enclaves – a territory completely surrounded by another territory.

Larry Bleiberg

Larry BleibergToday, one of the enclaves created by the Vennbahn covers just 1.5 hectares and contains a single farm. Others include small towns or sections of villages, the biggest covering about 1,800 hectares.

In the latter part of the 20th Century, traffic died down on the once-crucial rail line and a preservation group briefly tried to operate a tourist railroad. But in 2013, the former railway found new life when it was dedicated as a 125km paved bike path stretching through Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg. Cyclists now come from across Europe to pedal past medieval towns, nature reserves and misty farm fields dissected by centuries-old hedgerows. They also marvel at the preposterous border they're weaving in and out of. But the locals rarely pay attention.

Christian Strutz, a banker who lives in Germany, said it doesn't register that he's leaving his country when he drops by Meyer's restaurant, Nicki's Imbiss, in German-speaking east Belgium. "It's very normal for us," he said, then stopped for a moment to think about it. "It's crazy – crossing the border for frites."

Larry Bleiberg

Larry BleibergIndeed, life generally flows smoothly across the international boundaries, thanks largely to the Schengen Treaty, which, when implemented in 1995, eliminated most internal European border controls. In one area, a German bus stops on a Belgian street to pick up passengers. In another, a postman must pass through Belgium every day to reach a German subdivision of small homes, and to pick up parcels left in a canary-yellow Deutsche Post mailbox.

But during the global pandemic, residents were reminded once again that they were straddling two nations. Inevitably, the Belgium and German responses to Covid-19 didn't completely align, which meant on some days proof of vaccine could be required for dining on one side of the border, but not the other.

Although it seems isolated, this region has repeatedly found itself at the crossroads of history. Charlemagne ruled his medieval empire from Aachen, where the Vennbahn begins. Later, Napoleon ordered the construction of a road linking towns that would eventually be connected by the railway. Hitler seized the region and rail line in 1940, and cyclists can still see the "dragon's tooth" concrete barriers that were part of the defences erected by the Third Reich to stop the advance of Allied tanks. Four years later, US troops fought their way past the barriers and reached what is today the enclave of Roetgen, which became the first German village liberated during World War Two.

After the war, the area saw action of another sort. Locals found they could make a tidy profit by smuggling coffee beans from Belgium into Germany, where the prices were three times higher, giving the region a new nickname, the "sinful frontier".

Larry Bleiberg

Larry BleibergSome carried the contraband across the High Fens, a preserved region of wetlands not far from the Vennbahn that's known for its moody weather and porous border. But most the smuggling centred on Mutzenich, one of the Vennbahn enclaves. The town now honours the criminals with a bronze statue of a man with a sack of coffee over his back crouching behind a rock in the middle of the road. Over a five-year period, the smugglers carried more than 1,000 tons of coffee across the border, bringing badly needed cash into an area impoverished by WW2.

Mayor Jaqueline Huppertz, whose father was involved in the illegal trade, jokingly calls the activity an "early type of regional development".

The coffee carriers played an increasingly brazen cat-and-mouse game with authorities that sounds straight out of a Hollywood thriller. Men would travel by foot, bicycle and car, even stowing coffee beans in an ambulance and a hearse. When police gave chase, the smugglers dropped sharpened metal spikes on the roadway to stop the pursuit. The German authorities, who were using specially equipped, high-speed vehicles, responded by attaching a plough to the front of their cars to clear the hazards, a creation locals called a "broom Porsche".

Larry Bleiberg

Larry BleibergUltimately, about 50 of Mutzenich's citizens were caught and imprisoned near Cologne; a blow to the small town, which lost its economic livelihood and a such a large chunk of its male population that its municipal football team couldn't compete because it lacked players.

Many of the smugglers had donated money to help rebuild Mutzenich's war-damaged church, and the town's Catholic priest visited the inmates in prison to plead for their release. "Even today, this church is popularly known as St Mocha," the mayor said.

Ultimately, the men received reduced sentences, possibly because German authorities realised that the town might eventually vote in a referendum to join Belgium, Huppertz explained.

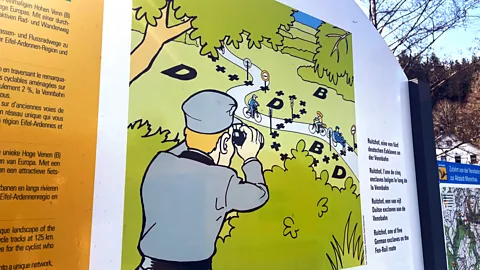

Today, the border is wide open, and the only indication you are entering a different country might be an easily overlooked street sign. Along the side of the Vennban, an occasional concrete marker sticks out of the weeds, marked B on one side and D on the other, abbreviations for Belgium and Deutschland. But the most convoluted border is the stretch near Meyer's chip shop in Raeren, Belgium.

Larry Bleiberg

Larry BleibergAfter eating my share of frites, I embarked on an international journey, stepping off the pavement to briefly leave Belgium and then dart across German Highway 258 to reach the Vennbahn, which put me back into Belgium again. I entered a trailside restaurant, Kaffeefee, which gets its electricity and water from Germany, although the business is regulated and licensed by Belgium. Café owners Waltraud and Norbert Siebertz live another 200m further east in Germany.

Waltraud said most of her customers are typically cyclists who have no idea where they are. "The criss-crossing and zig-zagging is quite a surprise to them – in a special way. They think they're illegally crossing the border."

After she serves them a beer or cappuccino and perhaps a cherry strudel, she offers the riders a bit of advice. Although the trail itself is in Belgium, they're actually much closer to German cities and services. "If they have an accident, I tell them they should roll to the German side," she said, "because the ambulance will come faster."

Places That Don't Belong is a BBC Travel series that delves into the playful side of geography, taking you through the history and identity of geo-political anomalies and places along the way.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.